As someone known to paper walls with maps, I’m loath to recognize that these representations of world beyond us can cause serious problems. But some maps have had lasting, serious consequences, perhaps none more so over the past century of American life than the residential 1930s redlining maps preserved by the University of Richmond, a collection that includes the map of Duluth that inspired this piece. (I was routed here by one of the city’s annual Housing Indicator Reports, which often involve fun research digressions beyond the rote reporting of statistics for various planning areas.) The urban planning field has, for some time now, been on a noble quest to educate the world about what these maps have wrought.

These maps come from the Home Owners Loan Corporation, or HOLC. HOLC drew up these maps to designate the safety of making loans in certain neighborhoods in cities across the country. It was part of a New Deal push to create consistent, predictable, non-predatory lending practices for home sales, thereby avoiding the disastrous wave of foreclosures that came along with the Depression. Its maps were also one of the most effective non-coercive tools for racial and income-based segregation ever devised by any government anywhere.

These maps, which color-coded neighborhoods by their desirability, basically walled off certain areas for development (“redlining,” in planning parlance), all under the guise of a well-intentioned program to help homeowners. They also included brazen designations of neighborhood desirability based on the race or ethnicity of their inhabitants. The HOLC-enabled postwar suburban housing boom was one of the least free markets ever devised, and it had a fascinating jumble of consequences to both lift the wealth of a vast swath of the (white) working class and shut out a portion of the country from ever enjoying those benefits.

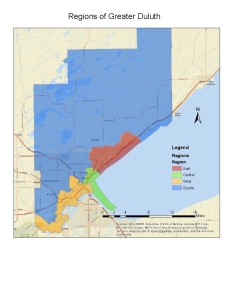

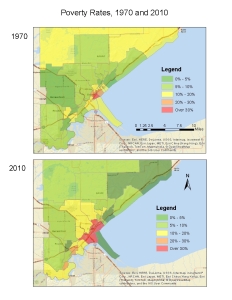

Some parts of Duluth’s urban history follow standard narratives on HOLC-age development. The ring around downtown, where significant early construction happened, remains one of the poorest areas of the city today. From there, the east side follows a fairly steady transition up the income ladder into Congdon, a change I can still see every day when I go for runs around my current home in Endion. (It’s amusing to see Endion get labeled “generally…declining, many of the old houses being transformed into small apartments and duplexes.” I’ve heard some people bemoan the neighborhood’s transitional status as if it were a trend brought on by college students in the past 20 years, when in fact it is a stable equilibrium dating back nearly a century.) But at the same time, as the little chart next to the map shows, Duluth’s urban form breaks down from the prescribed theory more than in many other cities. A substantial part of Duluth a certain distance from the core that is supposed to be “in transition” is not actually in transition, and the outlying “residential zone” saw basically no new development at this time, with its only housing being stuff in the lowest tier out in Gary-New Duluth and Fond du Lac.

Some parts of the city have also changed substantially since the New Deal era, and not always in predictable ways. I was fascinated to see that the bit of Lakeside where I grew up in a 1920s mini-foursquare, which now is one of the hottest real estate markets in the city, was “definitely declining” at this time. A chunk of Duluth Heights, which now also ranks fairly high on the income scale, was a total no-go zone for HOLC loans, as was Park Point. A number of other red zones on this map are basically non-residential now. The I-35 corridor follows a series of red zones, as interstate highways did in most urban areas; poor people are always the easiest to displace for massive infrastructure projects, and the U.S. became very good at that in the 50s and 60s. There is very little correlation between yellow districts and the current quality of the housing stock; yes, some remain, but just as many have flipped into comfortable middle-income areas, and not just those on the east side. It’s not unfair to conclude that the boundaries drawn on this map, while sometimes predictive, were in no way destiny for Duluth’s ultimate housing development.

As usual with Duluth, the simplest explanation for this is geography. Duluth grew outward along the ridge and lakeshore instead of in concentric rings, with development squeezing out here and there where terrain allowed. The city also absorbed a few older towns such as Fond du Lac and Lakeside, which may explain HOLC’s skepticism of their housing stocks even though those would normally be destinations for the next wave of development. The neighborhoods that had some room to grow outward from their 1930s limits, like Lakeside and Woodland and the Heights, had a chance to diversify their housing stock and evolve. The plodding pace of Duluth’s growth over the 20th century, oddly enough, kept some neighborhoods from filling out too quickly, and also invited updates to the existing stock to keep it viable for a sale. Those complex neighborhoods are a vital part of Duluth’s story, and a reason why this city has not gone down the road of a Flint or a Youngstown, where nearly all of the money fled the city proper.

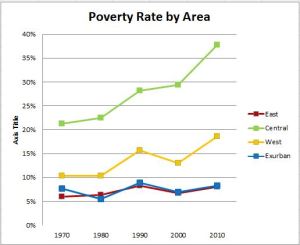

Another explanation comes in the racial and country of origin stats tucked away to the right of the map. Despite the map text’s frequent concern about “negroes” occupying certain areas, this shows Duluth was over 99 percent white in the 30s and 40s. But in 1930, fully a quarter of Duluth’s residents were foreign-born, and while that figure had dropped to 20 percent by 1940, that is still far higher than it is today. Duluth was a city of immigrants. Idle speculation might lead one to suspect that steady decline in the immigrant population over the middle of the 20th century (which correlates with statewide and national trends, as driven by U.S. immigration policy and global economics and politics), coupled with a fairly negligible rise in the population of people of color, would have been an equalizing force in Duluth’s housing market. By the 1970s, there was nowhere in town where there was much of the immigrant stigma that comes out in a few of the HOLC descriptions of west side laborer neighborhoods. Duluth at that time was the perfect all-white control in a national experiment in urban housing markets. And yet, the 2016 Duluth HIR report lays it bare: every one of those neighborhoods that had a description about immigrants or African-Americans in the 1930s remains low-income, even if many others that were in the same class as them back then have now flipped. That legacy, somehow, endures.

I would still, however, venture that the greatest reason for Duluth’s divergent neighborhood paths, one that captures both its old HOLC maps and its current east-west divide, is a structural economic change. Pre-war Duluth wasn’t some bastion of equality, but there were two distinct economies: an immigrant-heavy industrial working port on the west side, and a downtown and east side dominated by a white-collar class and its attendant lower-income service economy. One of these got absolutely decimated in the 1970s and 1980s. The other plugged along, certainly damaged by the trend on the other side, but had much more staying power and adaptability.

Now that it’s unrecognizable from what it was a couple of generations ago, I don’t think many of us moderns fully appreciate the complexity of Duluth’s old blue-collar economy. People with some sense of the history can tell you that Morgan Park (which doesn’t even register a color on the map) was a company town for U.S. Steel, but the map text describes Gary in much the same way. People actually used to live down in the port and industrial areas below the freeway near Denfeld, in a neighborhood known as Oneota. But I was most fascinated by the note in the area around Denfeld, which outranks places like Lakeside and Woodland and Hunter’s Park on the HOLC map. The residents of the Denfeld area, the text explains, are “salaried persons from nearby industrial plants, business and professional men of the west side of the city.”

That line about West Duluth reminded me of the extensive time I spent doing some interviews in Silver Bay, a company town built by what was then the Reserve Mining Company. We have this habit of thinking of blue-collar work as providing stable working-class jobs with modest incomes that allowed a family to get by, but to hear the Silver Bay old-timers tell it, company towns were some of the most rigidly segregated in America, at least in terms of income. Subtle features set apart seemingly identical homes, and management clustered in certain areas. There have been, and continue to be, many very lucrative jobs in industrial work; what set the pre-war era apart was that management was on the ground nearby, not out in relative suburbia (or in some other state or country at a hedge fund or holding company, though even in Duluth, there’s an old line about the city being Pittsburgh’s westernmost suburb). In industrial Duluth, that area for the blue-collar elite was the West Duluth neighborhood surrounding Denfeld High School.

Nowadays, the very notion of a blue-collar elite seems bizarre, and a perfect storm of conditions weighs on the west side housing market. If neighborhoods that age at different rates are far more likely to hold up over time, the more uniform ones—which company towns tend to be—have the misfortune of aging into obsolescence at the same rate. Those west side neighborhoods were also trapped between a river and a ridge, unable to find easy escape valves for steady outward development as in Lakeside or the Heights; instead, it had to leap up the hill to Piedmont (another neighborhood with well-diversified housing that doesn’t register on the HOLC map) or beyond the city limits. Most of those immigrant-heavy neighborhoods, where stigmas apparently lingered in ways they did not for areas occupied by native-born Americans in similar job classes, were toward the west side. It’s also just easier to commute from further away now. Throw in a two-decade crisis of mass layoffs and unemployment and plant closures, and it all starts to come together.

This isn’t all doom and gloom. The area around Denfeld is still comparatively wealthy for West Duluth, with some historic older homes. Eastern Lincoln Park, colored a respectable blue in the times of HOLC, has seen real estate values start to rise again after many decades of stagnation. Some growth along the river corridor has occurred, and room for more remains. As my friends at the Port Authority would ask me to remind the world, Duluth’s blue-collar economy is also far from dead: it may look very different, but the city still moves vast volumes of cargo and has a thriving industrial sector that usually pays a solid salary. The changing nature of industrial work, combined with the attractiveness of well-paying jobs that do not require vast loads of student debt, are starting to change some narratives about a once-stigmatized line of work.

But the ravages of deindustrialization tell a story that HOLC maps alone cannot, and join up with cultural clashes and geographic barriers to explain why cities come to be the way they are. Causes are rarely singular, and momentum did the rest. While real estate agents no longer use maps with explicit racial or immigrant-skeptic language, there’s no shortage of coded ways in which the real estate market designates the desirability of certain neighborhoods. These tools range from practical concerns about returns on investment to the asinine practice of grading everything that goes into public schools on a 1-10 scale, a tool now ubiquitous on any real estate aggregation site. We still live with the consequences of century-old maps, but the ways in which we build our economies and the stories we tell about our towns will decide their futures.