Day One: The All-American Road

My friend and I are on our way, ready to discover what we can of a country across two weeks. The trip begins with a gentle wind down the Minnesota River, through small towns whose names I know but which I’ve never seen. For the most part, they’re well-appointed, and we don’t pause to ponder them. We’ve seen a few Minnesota farms in our lives, and we’ll see more again before this trip is up. We plow on beneath a low sky, pick up I-90 in Worthington, and have lunch alongside a cornfield just past Sioux Falls.

In South Dakota, the twin ribbons of road undulate over rolling hills, slowly but steadily rising upward. One of the few pauses comes at the Missouri River, here wide enough to be a lake, and with an unnatural, greenish tinge. In time, the Badlands appear, the green grass falling away in cliffs and along buttes with such precision that it looks like they’ve been mined out of the plain. Ten thousand signs alert us to the presence of the Corn Palace and Wall Drug (we skip both), but just one sign gives any indication of the Pine Ridge reservation, which we skirt past. Just beyond these kitschy frontier towns lies one of the most destitute corners of America, a desolate and poverty-stricken zone where the future is as bleak as in any inner city. Drive down this highway, however, and you’d probably never know. Aircraft and helicopters buzz over us at the Ellsworth Air Force Base just outside of Rapid City, and after a bypass around the largest outpost in western South Dakota, we come to the Black Hills.

We climb into the hills, made dark by their scores of ponderosa pines. My first recollection, curiously enough, is of the Mexican highlands: dry pine forests, crowded winding roads, and an endless string of attempts at tourist attractions the entire way. These let up some when we enter the national forest, but there’s still a steady stream of them intermingled with signs warning us of bighorn sheep. Many of the attractions seem frozen in a different time to a couple of urbane city kids, but the culture that produced these roadside curiosities is alive and well beyond our limited cosmopolitan world. We eat it all up, too.

We pitch our tent a short ways north of the main highway. Home for the night is the Sheridan Lake South National Forest Campground, just north of Hill City. It sits among the pines along a small lake, and its whispering breezes evoke the Boundary Waters for us Minnesotans, though the RVs just down the way are a new wrinkle. We set up our tent and head into Hill City for dinner. We pass a series of wineries; we’ll have time for wine later. Instead, we end up on its Old West main drag, and we dodge motorcycles (Sturgis is just north of here) for dinner at the Bumpin’ Buffalo, which has a fairly empty deck with a view of the town. Further underscoring the Mexican instinct, we’re serenaded by the cowboys singing about cerveza in mediocre Spanish at the Mangy Moose across the way. Satisfied, it’s on to Mount Rushmore.

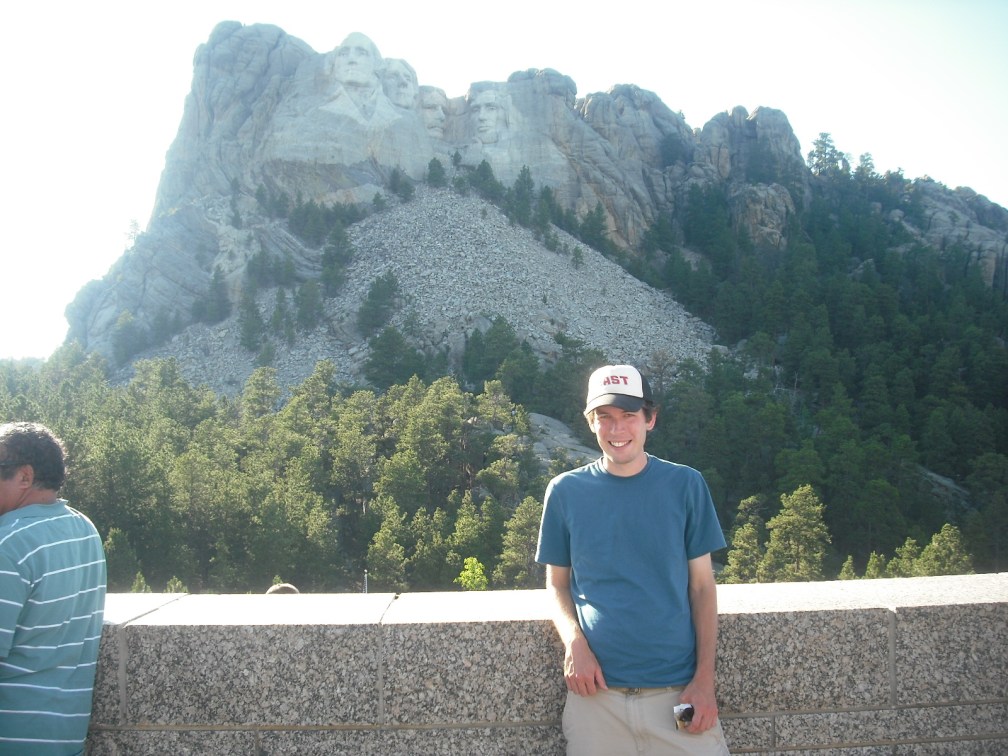

We come at the mountain from the south, and get a profile view of George Washington before coming around to fork over a heap of cash to the National Park Service for the privilege to park. We head up an avenue of flags and concrete arches to behold the quartet of presidents, all gazing over the valley below. Rushmore is so legendary that it seems almost small to me upon first sight, but even from our considerable distance, it’s a marvel of sculpture and ambition. I now appreciate its remoteness, and what Gutzon Borglum and company went through to sculpt this into being. The site museum adds some background, and the short walk back out passes some six thousand or so boy scouts. Bruce Springsteen serenades us as we drive away.

We swing south through the Hills toward the Crazy Horse memorial, still very much a work in progress; at $11 a person, we sheepishly snap a photo from a distance and instead drive on for a loop around Custer State Park. We work our way back up the Needles Highway, a narrow, sometimes precarious stretch of road that winds endlessly through the hills at a painstaking pace. Before long, however, we’re rewarded: the road climbs up into a forest of stone towers, culminating in the Cathedral Spires that support the ceiling of these hills. The view extends all the way back to the plain from which we came, the Badlands now illuminated in setting sun. The golden glow catches the top of the spires, and after every turn we’re compelled to stop again and jump out for another look. We inch through a few one-way tunnels, one of which is blocked up by some sheep; a whole herd of them dances down the mountainside, and we get a moment to admire their scraggly, shedding winter coats.

It’s nearly dark by the time we’re back in camp, and we linger down by the water for a little while before we crash. The stars, no doubt, were pristine, but in midsummer the sunlight lingers until late, and between our exhaustion and a rising moon, we have no real chance to gaze upward. Day one is done, a complete rush into a West that, while still vast an empty and hauntingly beautiful, is no frontier. It’s now an attraction, with Custer and Crazy Horse, those best of old friends, together on road signs, directing us onward to the next attraction. The Black Hills are the ultimate road trip destination for a car-loving country, distinctly American in so many ways. Yes, it has a side to it that produces t-shirts of Sarah Palin and Donald Trump together on a Harley, but it also brings forth a simpler era and nostalgia for a family on the road together, off to see beauty and building some memory they’ll always have. A fitting start to our journey.

Day Two: Dispatch from Deseret

We’re on the road early again the next morning, passing back through the Black Hills before coming into the high plains of Wyoming. The Equality State (so called for its early provision of women’s suffrage) is, for much of its expanse, a vast tract of nothingness, and we spend the majority of our day traversing it. It starts out as high plains, with ranches here and there. We cruise down the desolate federal highways, the towns rarely more than highway junctions. It’s nothing but space, and I have newfound respect for the old natives who called it home and the settlers who crossed it without asphalt and air conditioning.

The road southwest from Casper offers a little more scenery. State Highway 220 travels down a valley with the North Platte River at its start, weaving along the longest expanse of water we’ve seen since the Missouri. We have lunch at Independence Rock, the halfway point on the Oregon Trail, still covered in pioneer graffiti and evoking memories of cholera outbreaks in the old computer game. In time, we come to I-80, which for a stretch is even duller: gone are the layer cakes of colored rock, and we’re left with steady marches of empty green hills. A sudden squall beyond the Red Desert slows the endless convoys of trucks, and the downpour washes away the graveyard of bug guts on our windshield. We pass a few more vaguely familiar Oregon Trail locales: the Green River, Fort Bridger. To the south, the Uintas rise, their whitish peaks perhaps still bearing some snow. The land grows slowly greener, and we understand why the Mormons, in exodus on this very route a century and a half before, thought they might finally come to a promised land.

The engine protests some as we push up and down passes through the Wastach Mountains and snake past the ski slopes of Park City. After a twenty-mile descent, we’re in Salt Lake, our largest city since Minneapolis, suddenly teeming with late rush hour life. We check in at an Airbnb in the suburb of Bountiful, whose chief bounty is a neighboring oil refinery. Our host, a jovial Mormon ready with suggestions, tells us we can catch a Mormon Tabernacle Choir rehearsal in Temple Square. Intrigued, we head back into the city, though we’re distracted by the stunning state capitol first. Other capitols can match its size and grandeur, but few can equal its commanding position on a hill over the city, and its white-and-grey marble has a pristine quality absent from the sandier stone in the Midwest.

We hike down the hill to Temple Square. It’s in the upper 90s, but dry enough that it feels nowhere near so hot. The Latter-Day Saints have built themselves a lush marvel of a plaza, and we slowly approach the temple along fountain-lined promenades, the archangel Moroni beckoning us in. Mormon elders are on hand to explain some history, and direct us to the concert hall, which is so overcrowded that a line has formed, and the coordination of the line leaves something to be desired. After a wait, we make it in and catch a few songs from the choir. They’re brilliant, as we’d expect, even amid the din of bored children and cell phones. When we emerge, the line for this mere rehearsal is wrapping around the square. Nonbelievers aren’t allowed inside the Mormon temples (of which there are just 50 or so worldwide), but a visitor’s center gives a few glimpses of the events inside. Famished, we leave the complex and past a statue of a perplexed Brigham Young gesturing toward the Zions Bank tower across the street.

Salt Lake is built on the vast scale of cities of the West, with streets the width of eastern freeways and a rigid grid of numbered streets. Still, the space allows for innovation: there are bike lanes, a new light rail, and a fleet of pedicabs scurrying around downtown. It seems clean and orderly, as the LDS capital should be. Still, Salt Lake is surprisingly non-Mormon for Utah; many of its establishments could be anywhere, and we find a bustling brew pub to our liking for dinner. Day two closes with further examination of the Mormon faith, and a fair amount of respect on my part: they’ve built a remarkably strong institution that supports a distinctive way of life, but yet their integration with everyone around them remains impressive. Others who are in this world but aspire to ends beyond it have something to learn from the Latter-Day Saints, whatever we may think of their theology and nametags.

For now, though, it’s far too late already, and the wastes of Nevada await tomorrow. Onward to San Francisco.

(Part II)