This is the third in a three-part series. | Part 1 | Part 2

On the second to last day of my road trip, I cross South Dakota from southwest to northeast, almost entirely on back roads. I start in the Pine Ridge Reservation, which I expect to be jarring. It is.

The first markers of the new world I enter are the roadside markers reading “Think” and “Why Die?” While they are part of a statewide program to memorialize drunken and other reckless driving deaths, they are legion on Pine Ridge. Trailers begin to appear alongside the road, almost all in a state of decay, some fitfully patched up, others crumbling into these hard, rolling hills. In the town of Oglala, they just densify, each yard collecting broken down vehicles, mined for parts to keep one running. Drivers honk at the stray dogs who run in front of cars. A few men walk down lonely stretches of highway with no obvious aim.

The town of Pine Ridge stirs to life on this Sunday morning, a few kids ambling up streets and a group congregating outside a church. The reservation’s schools and health center at least look shiny and new, and the town now manages to offer some basic necessities in business and a few apparent research operations or other outposts from the outside. But it is still a tenuous borderland, still struggling to resist the entropy and despair that hang like a pall over Pine Ridge. There is one growing type of business that shows sign of new entrepreneurship: cannabis shops.

A few miles further east, I come to Wounded Knee. Here, in December 1890, over 140 Sioux camped beneath a white flag were slaughtered by the US cavalry. The massacre was the final blow in the Plains Wars and the end of an era, the frontier closed and reservation life made universal. Whispers of a mobilizing ghost dance spooked the Army, and after a single mystery shot, the guns above the creek blazed indiscriminately, killing Native men, women, and children, along with a number of US soldiers through friendly fire in the bloodbath below.

Today, a single sign by Wounded Knee Creek marks the site of the massacre, and a still-active cemetery atop a hill hosts the mass grave at its center. All is quiet when I pull up, but my arrival sparks some activity. An older man walks up the backside of the hill, introduces himself as the cemetery’s caretaker, and shares its history. His great grandmother, he says, is the one who showed another Sioux chief the blood coating the snow a few days later. He is reverent, adds some words in Lakota, though he also laughs easily as he talks of his grandchildren, for whom he needs to buy some Pampers.

Next, a younger man in a well-loved Seahawks jersey joins him. He adds some details on the 1973 occupation of this site by the American Indian Movement and subsequent standoff with federal forces. He had broken out of here to go live and work in Pipestone, Minnesota, but he is home to help restore water to his mother’s trailer down below the hill. He sells me a dreamcatcher. As I leave the site, two women with a young child arrive and begin setting up a table to peddle additional wares. For a variety of reasons I normally avoid giving handouts, but I leave Wounded Knee with a lighter wallet and no qualms about it.

Over these past two hours I have borne witness to an American moral disgrace. In some ways the tales of Native resistance and a delicate dance with an unbeatable government power take me back to the highlands of Chiapas in Mexico, right down to the vendors profiting off queasy, sympathetic tourists like me. But the affluence not far up the road seems to have particularly perverse effects on Pine Ridge, where residents can buy into one or two of the markers of modern American life but none of the rest, or are left with the detritus of a throwaway consumer culture and the accumulation of failing junk. I could haul in statistics on astronomical unemployment or obscene maternal mortality or life expectancies in line with the bleakest corners of sub-Saharan Africa, but my eyes are enough to capture the depths of the perdition here. Forget becoming great again: the US will be great when it can prove Pine Ridge is not a permanent state.

When I drove west in 2020, I struggled with questions about the state of the world, wrote moody fiction about a struggling soul who brushed up against the horrors of Pine Ridge. This time I drive freely, unburdened by what has been. I have borne witness, know I will find the words to capture this time on the edges of American life, a solo traveler drifting through and blending in with different worlds. I have a job in which I help chip away at the troubles in these lands, such as an outsider can. I am easing through, in control, pushing at edges and turning my eye my one great looming doubt, the place where my pursuit becomes tentative, comes up short.

As I go I listen to Hillbilly Elegy, now as good a time as any. The politics slip in here and there but the book is fundamentally an account of a broken boyhood, of one kid’s escape from a predetermined fate. JD Vance is the grandson of migrants (the irony drips through here), uncouth Appalachian Kentuckians who lit out for opportunity in an Ohio factory town, endured culture shock and their own demons but found ways, built lives. Two of their children lit upon upward trajectories, but Vance’s mother was the exception, the one who ran through men like tissues and lapsed into drugs. Young JD endures a constant rotation of father figures, jerked from place to place, unstable (despite some clear, precocious talents) until he finally lands in the place that has always been his most stable home: in with his Mamaw, the no-bullshit grandmother who sets a standard and holds him to it. She gifts him a world stripped of its ambiguities, clear in its expectations, no fleeting figures drifting through.

I feel stories like this deeply, am fascinated by how scars in youth can imprint themselves upon people. My own childhood was much happier than Vance’s, punctuated by a few acute jolts of pain instead of the near-constant anxious dread that probably made him the reflexive fighter that he is. Some scars linger, though, and he and I are not unaligned in some of our loose theories around the need for stable guides in a fluid world, of raising children to high standards, of the utmost importance of family life. How we have lived out that belief is very different.

I do not know if Vance has found the stability he craved with the choices he has made, will make no effort to judge his success or failure. But for my part there is no policy platform I would seek to impose on Pine Ridge to cure certain troubles of the soul, no rant about people whose views are different than mine. For me, before I ask what scenes like this demand that I do, I ask how I should be. In this case, the answer is to be a witness, to listen first, and then an attempt to uphold a faith in humanity through steady, daily work.

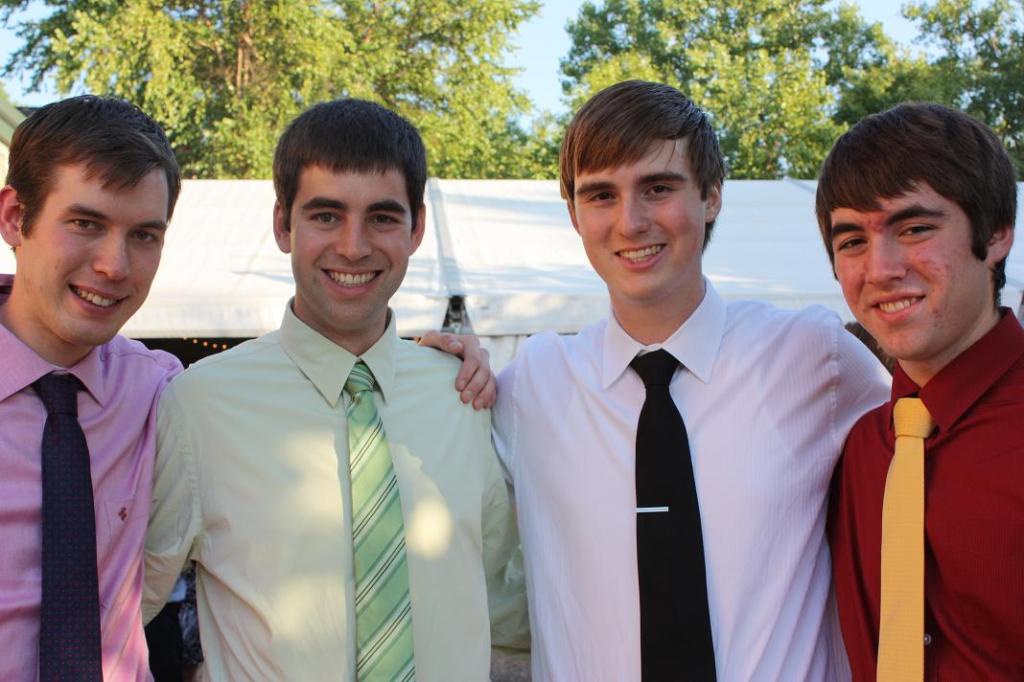

I have more pride than ever in the work I do because of some of the steps my office has taken over the past year to two to make good on some of these promises of greatness for people who deserve it. But the ties closest to home are still the ones that matter most. Trips like this one with an extended family are part of that work, bonds forged with people who are often not physically close but are some of my favorite humans. This whole year has been full of those journeys, and I cherish them all. And then there is my life in Duluth with my parents. Forget all the philosophical blather, forget the various expediencies: the foremost reason for my homing instinct in early adulthood was to live in joy with the two people who birthed me, even though our family unit is no longer. On that front, I have succeeded.

My project, however, is an incomplete one, and a gnawing void still looms as I dream of my own family life, my own investment in a future. What does it mean to want what I’ve been unable to find more than anything? It means I will pursue it with ever more vigor, with all the hunger, the joy, the panache, with everything I’ve articulated across all these journeys I take. I had thought this phase of life of outward journeys over the past few years may have been a distinct phase but now I understand it is in fact the project of a lifetime, an insatiable thirst for my world that will course through everything I do. I have built many of the necessary habits, slowly and fitfully over time. Whatever I might have believed before, I was never really ready. Now, I believe, I might be getting there. With that revelation I turn off the audiobook and coast into a Western sunset, my peace complete.