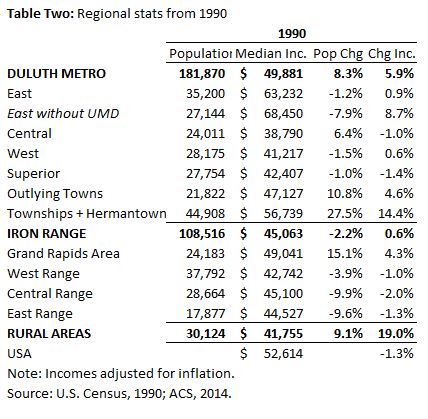

My new job has me hanging out with Census data some, and this spins nicely into a blog post that builds on some of my past studies of the Duluth area. Last time, I focused just on Duluth and outlying areas in St. Louis County. This time, I’ve expanded it beyond Duluth for a few reasons. One, there are parts of the Duluth ecosystem—most obviously Superior and Douglas County, Wisconsin, but also large parts of Carlton County and even bits of Lake County. The U.S. Census does publish statistics for metropolitan areas (MSAs), which they determine by county. However, when one of the counties in question is the size of Connecticut, as St. Louis County is, that’s going to wreck the data. As far as the Census is concerned, a cabin on Lake Kabetogama is in the Duluth Metro, and the area’s population lands around 280,000. For our purposes, I chop out everyone from the Iron Range on north, while also subtracting outlying bits of Carlton and Douglas Counties and adding Two Harbors, which the Census does not count as within the area. I was also curious about the Iron Range, a big region that I now work with on a near-daily basis, so I decided to pull its data, too. The end result: I have numbers on St. Louis, Douglas, Carlton, Lake, and Itasca Counties, and subdivide those five into regions so that we can draw some conclusions about different areas.

I subdivide the cities and regions in ways that try to explain a few things about them. To clarify this first table, “Outlying Towns” refers to communities like Cloquet, Proctor, and Two Harbors, which can stand alone as identifiable towns, but are within the Duluth commute shed. There are some differences between them, but they share a general trajectory. A separate, very large category is the wide swath of semi-rural area around Duluth and Superior, from townships to the north and south to Esko and Midway to the west. I include Hermantown and Rice Lake here because, unlike the cities in the previous category, they lack the defined town centers and history of planned development, and have indisputably arisen as outgrowths of the Duluth metro.

I divide the Range into four portions: Grand Rapids and its surrounding rural areas, the West Range (basically, from Coleraine to Chisholm), Central Range (Quad Cities and surrounding townships), and East Range (beginning with Biwabik and ranging all the way up to Ely). Apologies if anyone is offended by these groupings, deal with it; census tract names are also my own. Anything that doesn’t nest comfortably into any of the above categories gets lumped into the “Rural Areas” group, which I’m not going to devote a lot of attention to here: basically, they are shrinking, much older, and generally somewhat wealthier, probably due in part to the elevated age. Here are population, household income, and age statistics by region:

First off, for all the moaning about the struggles of northeast Minnesota in the current economy, the region modestly outperforms the nation in a lot of areas. Population growth may be lower, but income growth is higher, and household median income hovers above the national average. Some of this may be due in part to an older population; old people just generally make more money. But on the whole, I think these numbers are more of a reason for optimism about the area, at least when painting with the broadest strokes.

Also, to combat another common narrative, greater Duluth is not shrinking, nor flat in population growth. Since 1990, when the economy and population basically bottomed out, the region has had steady, modest growth, all driven by the outlying areas. Sure, it’s slower than national growth, but it’s real. The populations of Duluth and Superior have been remarkably stable over that 24-year stretch.

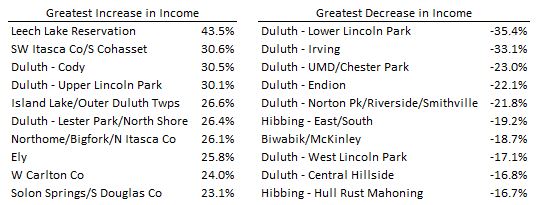

It’s not happy for everyone, though, and as Table Two shows, there is certainly evidence of divergence. Duluth, predictably, dominates both the top and the bottom of the income list, with pockets of great wealth and realms of substantial poverty. Those areas haven’t changed much since 1990—in fact, I was a bit surprised to see so little movement near the top, given the growth of the exurban areas—but the rich do seem to be getting richer while the poor get poorer. (See the table at the end for a breakdown by census tract.) This is less extreme on the Range, but it is noticeable in places, especially around Grand Rapids. It’s worth noting that the “Grand Rapids – South” tract split in two over this time period; I kept it together for consistency’s sake, but the southern, more rural part followed the trajectory of the wealthier areas around Pokegama Lake, while the more central parts slumped a bit.

The influence of Duluth’s colleges is also unavoidable. I split out East Duluth stats with and without UMD to show what an effect they have on incomes in that part of the city, while at the same time boosting an otherwise shrinking population, especially on the far west end of the area. Student housing has spread further afield, and the Census has also made more of a commitment to counting students where they live instead of counting them as living with their parents. (For my part, I’m not a fan of this decision, as I think it distorts things and gives an inaccurate account of the economic standing of students’ situations and of the area they live in, but no one asked me.) This leads university campuses to look like poverty-stricken wastelands; just check out the University of Minnesota campus sometime. Given the number of students, the income measured in a neighborhood like Lower Chester in Duluth is actually pretty substantial, even though it appears below average.

The Range, again predictably, is older and poorer than the Duluth area, and parts of it do worse than the national average. Grand Rapids—whose labeling as “Iron Range” is always a source of controversy anyway—also really carries the region economically. And while the East Range as a whole struggles, it could easily be split between the Ely and Lake Vermilion areas (which are growing in income, though still not rich, and fairly old) and East Range towns like Hoyt Lakes, Aurora, and Biwabik. These are among the worst-hit areas over this 24-year stretch, with the 2001 closure of LTV Steel in Hoyt Lakes looming large. Basically, the areas that have emerged as vacationlands are doing better than the more mining-dependent regions, and this is probably only even more true following the steel price downturn of the past two years.

It’s true that hospitality jobs don’t pay a ton. Ely and Tower aren’t getting rich off their recent tourism growth. But diversification does allow them to do somewhat better than their neighbors, and have something to fall back on in difficult mining times. The advantages are real, and are even more real around Grand Rapids, which benefits from being somewhat closer to the Twin Cities and on a couple of major highways.

Now, we’ll boil it all down to census tracts, which usually have 2,000-6,000 people and are roughly aligned with neighborhoods and towns.

The tract with the greatest income growth was a surprise to me: Leech Lake Reservation west of Grand Rapids in Itasca County. The other reservation tract, Fond du Lac, also did quite well for itself. Granted, these native communities are both coming from very low starting points, but it’s worth acknowledging that success, and taking a broader look at outcomes across the board in these areas. The other big gainers are mostly exurban lake country and a handful of Duluth neighborhoods that have seen some growth on the fringes plus, I suspect, some turnover as an older generation fades and gets replaced by a younger, upwardly mobile one. The biggest drops are in UMD tracts, a few of Duluth’s poorest areas, and in mining communities.

The age table reinforces the effects of the colleges. I’m over the median age in my own Endion neighborhood, proving once again that I am an evil gentrifier who is ruining the neighborhood. The oldest tracts, excepting the two central Duluth areas with large retirement complexes, are all very rural, and the top of the list stays very rural beyond the top ten, too. Central Duluth also trends young, and this is worth watching: are the people here upwardly mobile, and will they move up in time, and perhaps move east or west? Or is this another generation of entrenched poverty?

Answers to a lot of these questions will have to wait, but our friends at the Census can give us some clues. I’ll continue this series at some point, too. As an appendix, I here add the table with income stats on all 98 census tracts in the five counties I looked at: