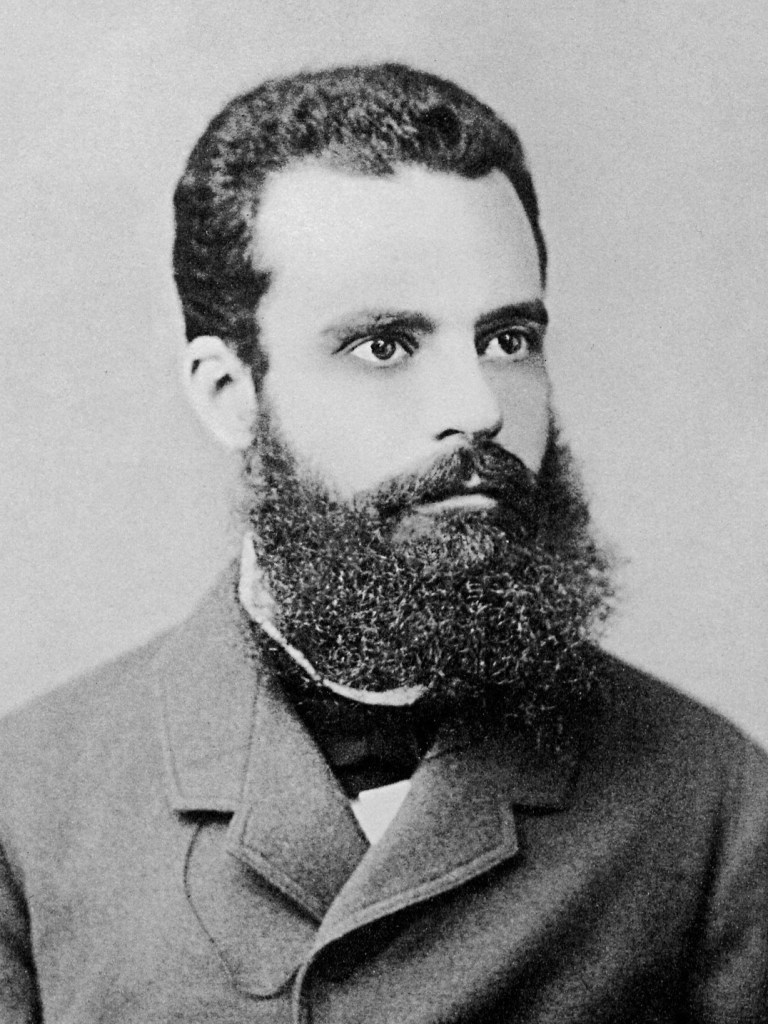

This dude is Vilfredo Pareto. He had a knack for finding patterns in human interaction, including some of the foundational insights into what we now would call sociology, and he wandered into my mind last week as I gazed in stupefaction as two old men lied, conveyed senility, and bragged about their golf handicaps in a competition to control the United States nuclear codes.

One of Pareto’s most useful concepts is called the circulation of elites. Basically, it says there’s a cycle by which vigorous people rise to power, hold it for a spell through a healthy balance of different impulses, and eventually lose that balance and tail off to be replaced by a new elite. The circulation of elites happens in any society, democratic or autocratic, open and free or closed and rigid. Just as some European nations seem to cycle through a new government every few weeks, the Soviets anointed and purged commissars; dynasties rise and then are overthrown, the Roman Empire conquers the world before it declines and falls.

The circulation of elites is a natural life span in any society, and it is reproduced on many smaller scales, much more often trading among competing power brokers and only very rarely taking form as a bottom-up revolution. (And when it does, those tend to be the bloodiest regime changes of all.) “History is a graveyard of aristocracies,” Pareto wrote, tracing how a rising, hungry elite that grabs on to valuable insights can dislodge a predecessor. The change often happens slowly, and then all at once.

How this circulation happens can be radically different, and the ease with which they happen is the difference between a stable, peaceable society and a bloody, chaotic one. Because the churn is always happening, a society needs methods to bring in new talented people and shed off those whose time has gone. It needs to break down the inherited status, clubbishness, and groupthink that can pervade in an entrenched elite. The most stable societies create pathways for talented people to rise and create institutions where no one person can stay at the top forever.

In the United States, that structure that does this has come to be known as a meritocracy. Meritocracy can be something of a dirty word these days; it is often woefully incomplete in practice, and even the best and brightest will sometimes fail at the greatest tasks before them. But it is still probably the best on offer, and on a global scale, a relative ability to keep the circulation going is more important than the absolute fluidity of a social order. A strong meritocracy sets a standard for achievement, creates its own internal ethical codes that filter out some of the most erratic people, and builds the norms and expectations necessary for a lot of people to live in relative peace. As a child of the American system I can poke holes at its incompleteness and internal flaws all day, but I still see the value it provides.

The beauty of a well-functioning democracy is that it provides a fairly responsive and usually nonviolent mechanism for circulating elites and forcing them to display some aptitudes to gain power. The American elite has always shown some capacity to circulate, and while the process can be lurching, it is often better here than in other places.* Leaders who suck get voted out of office, and if their replacements suck they also get voted out of office. The American two-party system, for all its flaws, creates two opportunities to bring forth new talent, both within each party and through rotations of power between them.

This is no less true today. Donald Trump certainly circulated an elite when he blew up a party that had become unresponsive to the electorate. He stabbed at the heart of the zombie Reaganism that was still carrying the Republicans through a world far removed from the one where Reagan built his majority. The fallout from that shift is still taking shape, and beneath all the Trumpian will to power the right is in a fascinating state right now as it invites in new critiques of the American state and tries to figure out what it stands for.

At the top, however, the Republicans are now overdue for another churn. The party has now put forward the same presidential candidate three elections in a row, a deeply divisive man now 78 years old, and the only reason we are not talking about his decline is the much more evident decline in the guy on the other side. The Republicans now exemplify the oldest of the Greek critiques of democracy: the ease with which a system stripped of any other mediating powers can degenerate into mob fervor and the charisma of a strongman. The more this party becomes a vehicle for one man and his family, the less likely its story is to have a happy ending.

The Democratic Party, more of a competition among competing interests than its counterpart, has proven a bit more structurally resilient. In 2020, a fractured field stopped its squabbling and got in line behind the guy best suited to dethrone Trump at the time. The party has a deep bench of interesting rising figures, including a bunch of Rust Belt governors who have directly attacked the causes of the 2016 failure, who could circulate up if given the opportunity. But the Democrats are still subject to the inertia of an old elite that can cost them dearly, both in the decision to line up behind Hillary Clinton because it was “her turn,” and now in the slow-motion train wreck of Joe Biden’s campaign that never should have been. Last week’s debate was, perhaps, an egregious enough peak to wake people to this fact, but it will still take true courage and inventiveness for Democrats to do what they have to do and find a new candidate.

Great people can shape history, but their moments come and go in a heartbeat, especially if they themselves do not change with the times. Knowing when to stand aside for someone new can take uncommon humility, or at least a clear-eyed understanding of one’s role and realistic chances in a broader drama. Ideally, a system should never let it come to that. But we are where we are, and anyone who wants to avoid increasingly ugly transitions of power had better root for some circulation of elites.

Image credit: By Unknown author – [1] [2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68615041

* Lengthy comparative politics student footnote: Some very autocratic societies can seem stable, but rarely do they come to happy endings. Despots can rule for a very long time through enough fear and control, but when they do finally fall, it can get brutal, as the Arab Spring showed. Imperial dynasties are some of the longest lasting regimes in human history, and while the monarchs and emperors make their divine claims, the brilliance of these systems lurks in the shadows of great palaces. Imperial China owed its stability to a deep bureaucracy that did circulate regularly, often forced by the castration of its most important functionaries. The absolute monarchies of Spain and Portugal ossified quickly, while the nimbler Brits created a system for regular changes in the Parliament behind the monarchial figurehead, and thus an obscure island built the greatest empire ever known to humanity. They even gave up that empire without a serious internal collapse, which, whatever else we may say about its colonial legacy, is a remarkable achievement.

Party systems can also do their own filtering and circulating, and single-party states can lock in the control for a spell. In the early-to-mid twentieth century, Mexico developed what Mario Vargas Llosa called la dictadura perfecta, the perfect dictatorship, in which the Revolutionary Institutional Party (what a name) just ran the show by tacking left and right with the mood of the country, careful to pay off just enough interest groups to keep everyone passably happy. Post-Mao China functioned in a similar way, as the ideology fell out of the Communist Party and the country exploded on to a path of remarkable growth.

But this single party road runs the risk of capture by either inflexible interests or a single strongman, and with no competing party to offer a realistic alternative, there is less of a check on these instincts than in a competitive democracy. Mexico’s regime eventually broke down, toppled by its own cruel reactions to a radical left and as it went broke trying to cover all its bases, though certain legacies of that era, like the single-term limits on office holders, are now saving graces for Mexico’s very imperfect democracy. China is now abandoning its ideological fluidity under Xi Jinping, a shift that is both worrying for short term global stability but in the long run leaves me much more bullish on the American position vis-à-vis its greatest geopolitical rival. Xi may do a lot of damage in the near term, but he is systematically weakening his party’s ability to adapt to changing realities, including his own eventual passing.